Geographies of Violence Against Women and Creating Safe Spaces in Inchicore

This is the eleventh in a series of blogs on 'Spatial Justice in Dublin 8' (SJD8 #11), as a contribution to Maynooth University Social Justice Week 2022.

In the world today, many women experience different types of violence, such as sexual assault, physical violence, and emotional violence. Violence against women (VAW) often starts in a place where women should feel the least vulnerable, their home. If a woman cannot feel safe in her own home, she cannot be expected to feel safe anywhere.

Spatial justice plays a key role in understanding domestic violence in the city, including in places like Inchicore, Dublin. The geographical contexts where women experience such violence matter, as do the possibilities for women to find safe places. For example, in parts of the city that have been systematically marginalised and oppressed by the state (see Duff SJD8 #9: ‘Activism and Housing In/Justice in Dublin 8’), working-class women may face multiple challenges when seeking help or support, such as finding secure housing, or getting access to healthy public spaces for herself and other family members. If she needs to go ‘outside’, she may confront the legacies of ‘chronic urban trauma’ (see Till, SJD8 #1: ‘Sustainable Communities…’), including economic decline and drug- or crime-related violence due to the lack of state support for maintaining the neighbourhoods in which she lives. Moreover, VAW has significantly increased during the current Covid-19 pandemic because of government guidelines, which have restricted movement and increased isolation (WHO, 2020).

In the next section, I describe how women globally and locally experiencing violence may struggle to call a suitable location home. In this context, the role of community activists are critical, and for this reason, the blog focuses mainly on the work of the Family Resource Centre (FRC) at St. Michael’s Estate in Inchicore, including the Women’s Outreach Centre which support women in need. I discuss the importance of the work of feminist activist Rita Fagan, who established the FRC in Dublin 8 with other community activists, to help women survive multiple tough circumstances.

Home: A Place of Stability or Fear?

For many people, ‘home is our base, a place that roots us to earth, give us stability, a place in which we feel comfortable and safe in’ (Heathcote, 2012: 3). Heathcote (2012) outlines how a healthy home should provide warmth, happiness, and contentment — what a home should be – but such a definition may be a gender-biased understanding of home. Woodhall et al (2014) discuss how women that have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) changes their understanding of the meaning of home to a place of fear. A space which is not created by love or happiness, but rather, by fear and crime, is more similar to a ‘cage, a trap, a site of fear and abuse’ (McDowell, 1999: 157) and no longer a place of security and warmth (Figures 1-2).

Blunt and Dowling (2019: 125) describe how home can be a ‘place of violence and abuse as well as comfort and security’. Their work points to the fact that the understanding of home has different meanings for people who experience IPV at home. Moreover, for many women who leave their intimate partners, they find it extremely difficult to ‘maintain their ideal vision of housing stability’ (Woodhall, et al., 2014: 258). In fact women that were interviewed described a stable home as both feeling safe from violence as well as having the presence of cameras within their residence (ibid). If in fact as many as ‘1 in 3 women have experienced physical and sexual violence in their lifetime’ (Mohan, 2021) from an intimate partner (Figure 3), more research is needed from the perspective of women experiencing IPV to create more inclusive definitions of home and housing stability. For this reason, it is important to learn from the work of local activists in tackling this pressing issue.

The Family Resource Centre and The Women’s Outreach Centre in Inchicore

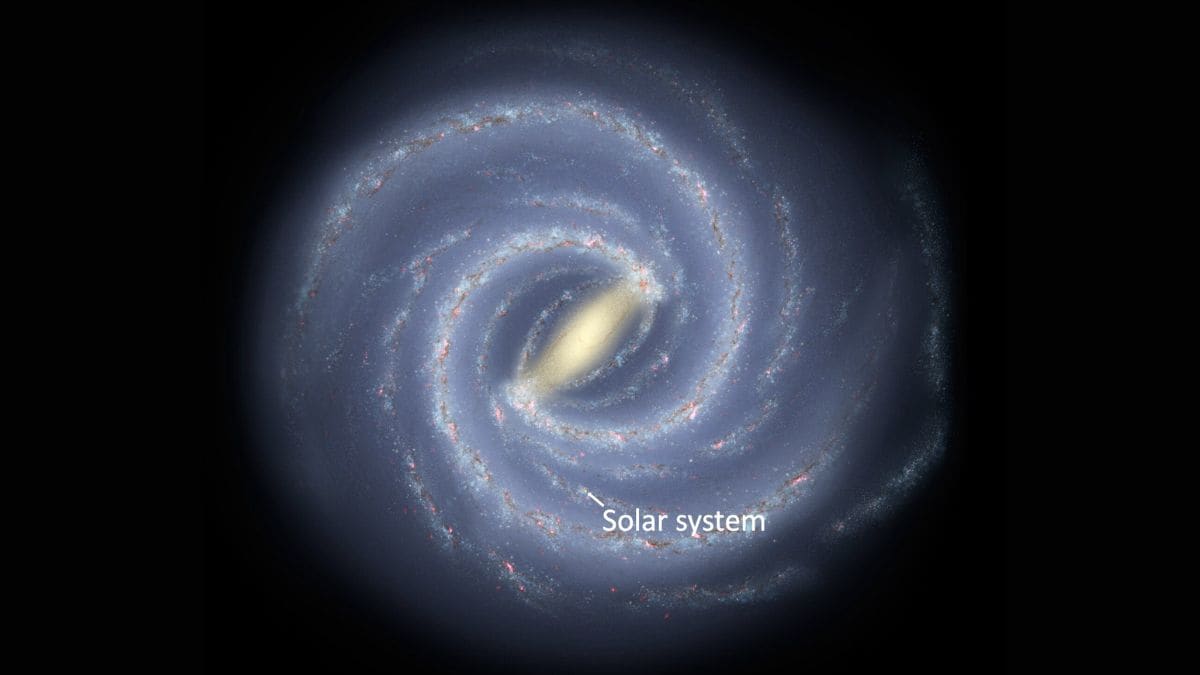

In our ‘GY607: Field School’ class last semester, we learned more about the reality of violence against women from a local perspective, specifically in Inchicore, Dublin 8, from Rita Fagan, a local community worker. Rita reflected on how, as a child, she spent many years watching her mother ‘going from door to door to check up on women to ensure they are in a safe environment’ (Fagan, 2021b). Such acts of kindness would later encourage Rita to help set up an organisation with other community members to ensure that women would have access to a safe place if they needed help. This women’s community project began to address the additional social factors in the community that potentially exposed women to violent acts, such as the ‘increasing levels of drug use, the high rates of crime activity, overcrowding and the economic crash, all factors putting women and children at extreme risk’ (ibid) (Figure 4). Their work led to the establishment of the Family Resource Centre (FRC) in 1986 by local women, which soon became ‘a space for people to come together’ (Bissett, 2008: 34) in a three-bedroom city council flat in St. Michaels Estate. Over the years the FRC has expanded to provide a wide range of services for the community, such as education, artistic programmes, and outreach support services.

Rita and other activists have carried out astonishing work to support women experiencing violence in the area. The FRC offers a safe space for all women to ‘come together and participate in the process to influence social, political and cultural change’ (Bissett, 2008: 34). A new center was introduced, known as The Outreach Centre, which was prompted by the murder of Mary Baily, a volunteer in the Resource Center. Mary Bailey visited a residence where a woman was being beaten by her intimate partner. As Mary intended to resolve the issue, the male figure acted out and assaulted Mary, resulting in her death. This serious act of violence became a moment of ‘realisation that men could in fact kill’ according to activist Aneta Koppehoffer (cited in Clearly, 1999, np).

The Outreach Centre (Figures 5 and 6) therefore became a service that supported women that are experiencing or did experience violence within their homes. This service has a 24-hour helpline that allows women to come forward in their own time, ‘ensuring safety for all women experiencing violence’ (Family Resource Centre Inchicore Dublin 8 Violence Against Women Outreach Service, 2021). The Outreach Centre allows women to access it themselves, which means they do not need to ‘phone a GP to get a referral, but instead make their own appointment in a place they feel most comfortable to speak’ (Fagan, 2021a), allowing the volunteers to share advice and support them especially during tough situations such as court. Moreover, when women do attend court following experiencing violence, they are assisted by numerous volunteers which work within The Outreach Centre, including Katie O’ Shea and Aneta Koppehoffer, who help women with court statements and attend court to show their support. This act of kindness was highlighted from the women supported by the volunteers, who stated that they feel much safer within their home after attending the service, resulting in a change in their understanding of home from a space of fear to a more positive one.

Figures 5 and 6. Standing Against Domestic Violence: The Outreach Centre in Dublin 8. Source: The Family Resource Centre Facebook Page.

We have seen that The Outreach Centre has carried out tremendous work within Inchicore, Dublin 8, but like every other service, it too has been faced with many challenges, especially during Covid-19. The current pandemic has introduced many restrictions to prevent the spread of the virus, including movement restrictions and isolation. These restrictions have increased ‘the risk of intimate partner violence’ (WHO, 2020) among women and children (Figure 7). The current pandemic has also had a major impact on the economy resulted in further job losses enforcing men to take their anger out on their partners exposing women to further risks of violence. The World Heath Organisation has suggested that with even more limited access to services that help support women, during the pandemic many perpetrators of abuse may use ‘restrictions due to Covid-19 to exercise power and control over their partners’ (WHO, 2020, np).

To help improve the safety of women during the pandemic, Rita and her colleagues ensured that The Outreach Centre was accessible to all women and children. Due to health regulations, volunteers needed to gain extra support from other organisations such as ‘Safe Ireland and the Community Foundation’ (Fagan, 2021a) to ensure the women and children would have their basic needs met in the context of increasing levels of domestic violence. Outreach Centre volunteers constantly ‘assured the women experiencing IPV that they were always there to support them’ (Fagan, 2021b), and continued to carry out tremendous work within the community to help limit the extent and scope of violence experienced towards women and children during lockdown and restricted movement.

It is clear to see that Rita Fagan and her colleagues carried out astonishing work locally within Inchicore, helping hundreds of women asking for support. Rita also wants to remind people about the prevalence of VAW not just locally but globally, by participating in the UN ‘16 Days of Days of Activism against Gendered-Based Violence’, an annual campaign that began in 1991, running from 25 November to 10 December around the world. This event marks a period where frontline workers, activists and other organisations find ways to raise the issue of gender-based violence every day for sixteen days globally. In 2020, a special event was held in the Goldenbridge Cemetery (see Thiesen SJD8 #4 ‘Dublin’s Urban Cemeteries’) and in 2021, the Outreach Centre collaborated with The Irish Museum of Modern Art, to launch their campaign through a moving opening night of remembrance, which included live music. People and supporting social groups locally and nationally came together lighting candles to honour the lives of the 242 women that were killed in Ireland from 1996-2021 as a result of gender-based violence (Figure 8). Many specific individuals were remembered, including Nicole Murtagh, who lost her mother to male violence in January 1996. The Centre drew upon their visual installation ‘And They Tell Me’ from their exhibition ‘Once Is Too Much’ to create a pathway of memories using the lilies, candles, music, and voices to recount the memories of the women. Joe and Tom Lee filmed the event, which is now also available in two parts as an online video to further raise awareness about VAW in Dublin and Ireland.

Conclusion

This blog has highlighted how the assumptions of ideal definitions of home as a place of warmth and happiness may be inappropriate to those who have experienced IPV. In the context of a ‘wounded city’ (Till, 2012), the work of feminist community activists becomes even more critical. This paper demonstrated how the work of the FRC Outreach Centre in Inchicore, with amazing volunteers such as Rita Fagan and Katie O’Shea, can have a positive impact on a woman’s life through helping her gain access to safe online and local spaces, and legal support, which, taken together, may change her experiences of a home to a more positive one. Domestic violence is tied to issues of spatial in/justice at multiple scales. By supporting women experiencing IPV at home, The Outreach Centre also creates a healthier community in Inchicore, as well as calls attention to the prevalence of VAW in the city and Ireland, while connecting in solidarity with other feminist activists globally through international actions.

— Liz Brophy

Liz Brophy is a Postgraduate Diploma student in the Department of Geography at Maynooth University. This blog post was developed from an essay for ‘GY607: Field School’ in Semester 1, 2021, taught by Professors Karen Till and Gerry Kearns.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Karen Till for her helpful feedback on earlier versions of this essay, and to both Karen and Gerry Kearns for their editing and support. A special thanks also to Charlotte Edwards, Elizabeth Burke, Teresa Murphy and Sarah Kirwan.

References

Bissett, J. (2008) Regeneration public good or private profit. Washington D.C: New Island Press.

Blunt, A. and Dowling, R. (2019) Home. London: Taylor & Francis.

Bucholz, K. (2020) Massive Rise in Gender-Based Violence Expected in Prolonged Lockdowns. Statista [online] 30 April. Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/21566/global-rise-in-gender-based-violence-covid-19/ (accessed 18 January 2022).

Clearly, C. (1999) Video to highlight against women. The Irish Times [online]4 February. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/video-to-highlight-violence-to-women-1.148672 (accessed 13 December 2021).

Fagan, R. (2021a) The Greatness of a Community is Most Accurately Measured by the Compassionate Actions of its Members. The Family Resource Centre CDP. Brochure. Dublin: Family resource centre.

Fagan, R. (2021b) Guest lecture and class conversation. For: GY607: Field School (Maynooth Geography postgraduate module taught by Professors Karen Till and Gerry Kearns, Semester 1, 2021), 12 November. Dublin: St Michael’s Estate.

Family Resource Centre St Michael’s Estate. [Online Facebook Page] Available at: https://www.facebook.com/frcsme/ (accessed 18 January 2022).

Family Resource Centre Inchicore Dublin 8 Violence Against Women Outreach Service (2021). And They Tell Me [Video]. Filmed by Joe and Tom Lee (25 November). Ireland: Joe Lee Studio. Available on YouTube in two parts at: https://youtu.be/yJl40JmHGT4 and https://youtu.be/yJl40JmHGT4 (accessed 16 March 2022).

Heathcote, E. (2012) The Meaning of Home. London: Francis Lincoln.

McDowell, L. (1999) Gender, Identity, and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies. London: Polity Press.

Mohan, M. (2021) One in three women are subjected to violence – WHO. BBC News [Online] 9 March. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-56337819 (accessed 18 January 2022).

Tellewin, H. (2021) Life in the Margins: Cultural Body Modifications and Gender-Based Violence. The HPHR Journal. [Online] Available at: https://hphr.org/blog-5-tillewein/ (accessed 18 January 2022).

Till, K.E. (2012) Wounded Cities: Memory-work and a place-based ethics of care. Political Geography 31(1): 3-14.

Woodhall, J., Wright, S., Daoud, N., Matheson, F., Dunn, J, and Campo, P. (2014) Establishing Stability: Exploring the meaning of home for women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Springer 32: 253-268. DOI 10.1007/s10901-016-9511-8 (accessed 18 January 2022).

World Health Organisation (2020) Covid-19 and Violence Against Women: What the Health Sector/System Can Do.[Online Report] Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/emergencies/COVID-19-VAW-full-text.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 12 December 2021).